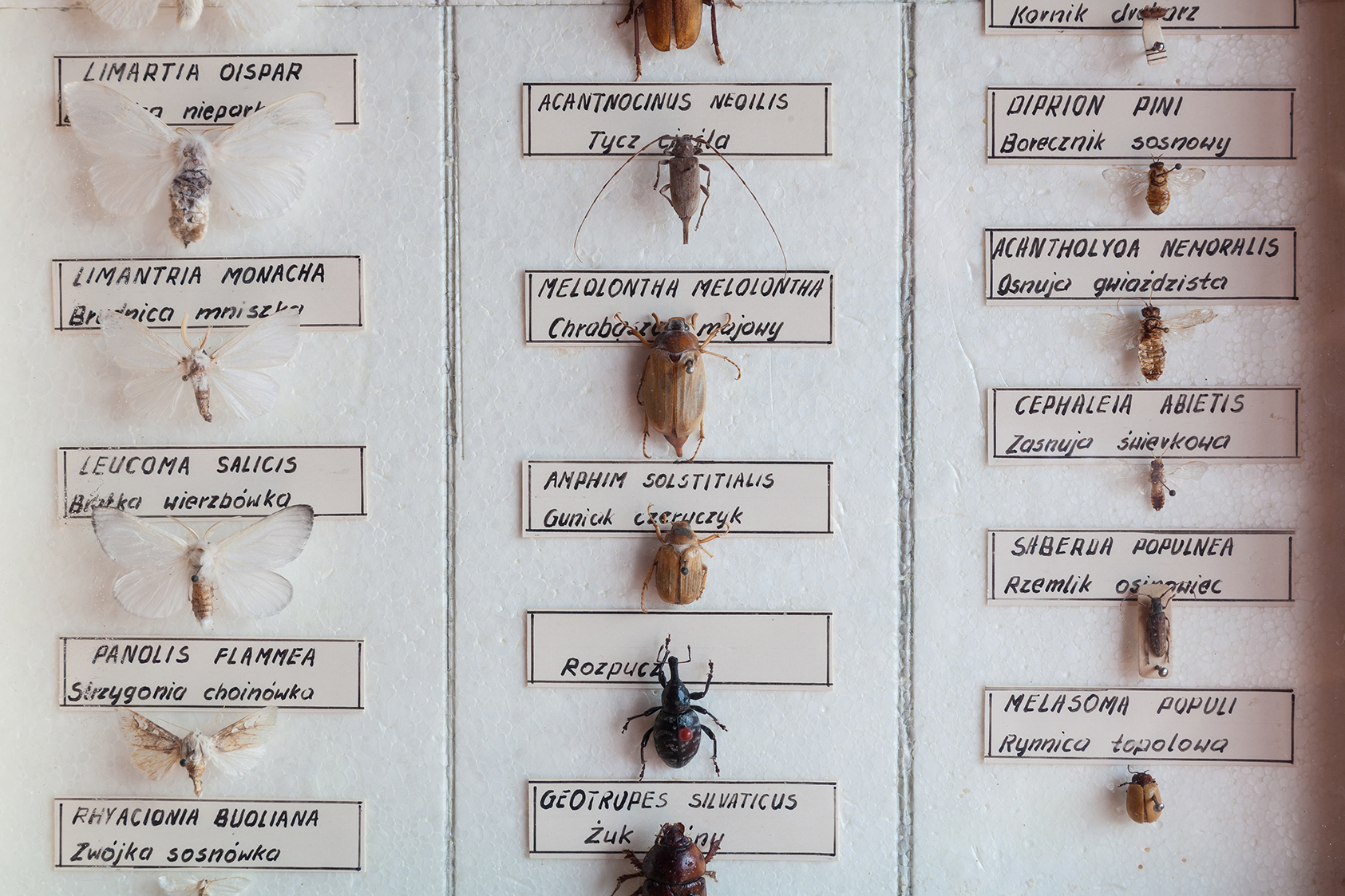

A bug hunter’s collection with some nice specimens (Photo: FreeImages.com/pi242)

Bug bounties for open source projects

Bug Bounties are a well established way to discover security flaws in software and services. Yet an attractive bug bounty program costs a lot of money and it takes a lot of time to set up and maintain.

Unfortunately, time and money are often in short supply in Open Source projects. Same here. In fact we had pondered the idea of a Bug Bounty before, but it took the Paranoids – the security team at Yahoo – to bring the idea to life.

The model we found may be exemplary: Take a big enterprise with a well established bug bounty program run by a professional team and include the open source software as an additional scope, while profiting from the smooth processes that are already in place. Another benefit, of course, is the third party bounty sponsor: Yahoo paid the bill and we fixed the bugs. A fruitful partnership with benefits for all CRS users.

Bug bounty platform provider Intigriti came in to make sure the right bug bounty hunters would join the program. Intigriti also did 1st level triage, moderated the content, organized calls, created special prizes, etc. All contributed to the program to make it attractive and fun for the hunters.

The setup was perfect.

CRS as a special case

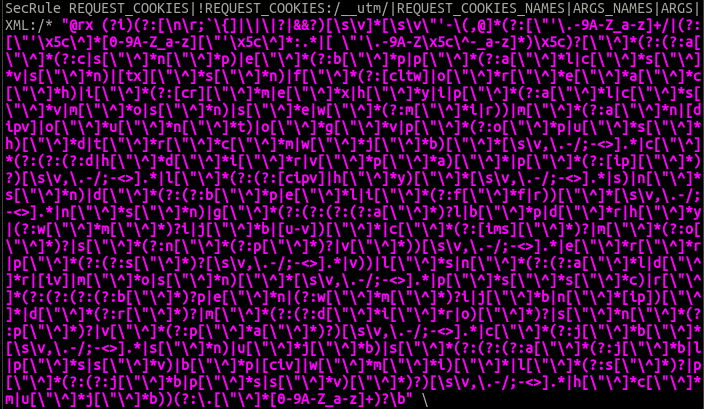

CRS is a bit of a special case when it comes to software. Our code consists of ModSecurity rules, which means regular expressions and directives in a domain specific language. So this is not your average python web service with bad input validation. It’s a crazy piece of code and a lot of people despair when they see our rules the first time.

A typical CRS rule with the machine generated regular expression

The reason the first attempt at a bug bounty failed was because none of the standard Yahoo bounty hunters were interested in digging into CRS for the occasion. One of them asked me why he would share a WAF bypass with us. I asked him why I would share a rule that detects XSS.

The second time around, Intigriti got involved and invited web application firewall specialists: people who had published WAF bypasses before. So we faced a completely different group of attackers and they left no stone unturned.

The triage challenge

When planning the program, we estimated our capacity to be at around two security findings per week. That does not sound like much, but it still means a conservative capacity of 100 findings a year. And that’s a substantial number for a volunteer driven project. Yet having received 175 reports often containing multiple example payloads overwhelmed our project and our security process. The number was so big that raising the pace for a few weeks did not change a thing. This was going to be a marathon and I and my fellow project leaders had to make sure it would not become a death march.

Meanwhile, the program wanted to get fast replies. Intigriti did an excellent job with first triage, but most of the reports were of high quality and passed that stage. They landed on our desk and we had to make up our mind about them within two weeks, so the program could be closed and the bounties paid out.

That was already very hard. But it got worse. With 175 reports, you need to group them. Grouping them by severity seems natural. Yet you need clear criteria to assign the severity and you need to get an overview of all the reports.

Needless to say, our existing criteria were not adequate for the amount of reports we were handling and getting an overview of 175 free form reports created difficulty. This resulted in a situation where more and more critical findings popped up. Things that looked quite innocent at the first pass suddenly became partial rule set bypasses and thus critical from our perspective.

And we also continued to identify findings that needed to be fixed upstream, in ModSecurity itself.

Critical and not so critical findings

An SQL injection may look horrible in a random piece of software, but it’s mostly daily business for us, since we deal with SQLi and similar application problems all the time. We are really strong with SQLi, but I have no doubt you can bypass our WAF rules with a well crafted SQLi payload. So if we receive an SQLi bypass in CRS we know how to deal with it. We don’t get overly nervous with false negatives as we get a lot of those: We close them one by one and then we move on with life.

The point is that the WAF is only an additional security layer in front of the application. And while we will try and block all the attacks, we do not have any illusions of our defense capabilities against a dedicated attacker. And even if a WAF bypass is bad, you still need a weakness in the application to have an exploit. It’s the defense in depth that gives you security and OWASP CRS is but one element in this defense architecture.

So an individual bypass is more or less daily business for us. The dangerous stuff is where you submit a payload A to disable the WAF so payload B goes undetected. We call this a rule set bypass or a partial rule set bypass. We defined these were the critical findings for us.

If you look at an individual finding in front of you, it’s relatively easy to decide if it’s a rule set bypass or not. With 175 reports it’s hard to make sure you do not overlook a detail or a variant that allows to turn a finding into a rule set bypass.

In the end, we identified almost a dozen rule/partial ruleset bypasses. Partial because only parts of the rule set were disabled or the attack was limited to POST requests etc.

So on the bright side, we were lucky there was no full ruleset bypass among the reports. But more than ten partial rule set bypasses was really bad.

Excellent cooperation with the ModSecurity developers

The cooperation with Trustwave – the company behind ModSecurity – and the ModSecurity developers from Trustwave Spiderlabs has been difficult in the past. But when dealing with the bug bounty findings that we forwarded to ModSecurity, the collaboration was forthcoming and supportive.

We had expected to enter an uphill battle here. But it actually went really smoothly. This was very important for us, since everything else seemed so difficult and overwhelming.

With the support of Trustwave Spiderlabs we were able to fix all the partial rule set bypasses by September 2022. They issued releases for ModSecurity and we backported our fixes to the 3.3 and the 3.2 release line.

It is unfortunate that many Linux distributions failed to pick up the ModSecurity and the CRS releases in the meantime despite CVEs and plenty of documentation explaining the dangers of the unpatched versions.

If you are a software developer yourself, you may want to look at the CVEs to make sure your software or the framework you are using does not make the same mistakes ModSecurity was making. There are interesting loopholes in the protocol that got exploited here.

A slow recovery

Before the program, we did not have a strict approach to security findings. We tracked them via email history and we did not follow a clear procedure. But at least we had a habit of creating unit tests for every finding we received.

With hundreds of payloads, this laid back approach stopped working. We started a spreadsheet, but the number of columns grew and the results were mixed.

Ultimately, we realized that transforming every payload into a curl call so we could reproduce and test it was a crucial first step.

This may sound so simple in hindsight. In fact, fixing a problem usually involves creating a curl call before you can fix it. But for the bug bounty findings, we started to create 500 curl calls as a batch before we attempted to fix them one by one or in small groups (at that moment about 3/4 of the findings were still open).

Thanks to our great sponsors we had money ready to pay one of our developers to pull this off in a two week sprint. Glad he had the time to do so.

Once that was done, we could start to assign reports to developers and they could get going immediately since they had a series of curl calls as a base for their work. This made all the difference.

We also developed a script that transforms a curl call into a CRS unit test. Another piece that adds a bit of comfort when fixing bugs.

Autumn was busy, but we made very good progress now.

The long tail of findings

OWASP CRS had scheduled a one week developer retreat for the end of October. We started the week with 40 open curl calls on Saturday and got down to a handful of them by Tuesday or so.

This is when we ran the loop over all the curl calls the first time and the results were depressing.

We had focused on reports with the assumption that the individual payloads within a report would have been closely related. So when we closed a report, we anticipated we would now detect all the payloads. Technically we had the curl calls to test this, but the process was not really well established yet. On top, many of the reports were maintained as github issues that had been created before we had the curl calls so the coupling between a report in the spreadsheet and the curl calls describing the individual exploits of the report was weak.

Long story short, we had worked like crazy to start the developer retreat with only a few dozen findings and after working 10–12 hours a day for half of the retreat, we were back at 50 curl calls we did not detect.

That was very sad.

On top, those developers working with the regular expression generator we were using reported that our tool set had reached a dead end. If we wanted to close the remaining findings we needed a new approach to the generation of the regular expressions.

However, the same developers were also very enthusiastic about their new plan and we got going immediately. Admittedly, some developers were visibly exhausted and I started to fear the worst for the project.

The new approach to the creation of regular expressions meant that we would abandon a venerable perl regex assembly library and transition over to a promising new GO library. We coupled this with a new tool called

crs-toolchain that allowed to write recipes with macros and includes to create our regular expressions.

Before we got going on the remaining bug bounty findings, we had to transfer dozens and dozens of existing regular expression snippets to the new format. Thanks to working in the same room at the summit, we got going quite quickly, even if the new format was on a new complexity level when compared with the old one.

The retreat ended, things looked promising again, but the road to perfection was still not clear. We realized that a dozen of remaining Remote Command Execution (RCE) findings were impossible to fix even with the new toolchain. We had to replace the architecture of some of the RCE rules with something better and the toolchain had to get one, two new features.

Given the exhaustion level of our developers, it is no surprise this took several months again. But then, on a beautiful day in February 2023, a day I spent in bed with severe fever, we ran the loop over all the curl calls again and we were good.

175 reports fixed and 511 individual payloads detected. What a relief. If you are interested in the details, we closed five payloads with status Won’t Fix since they are either too exotic, not really an attack or they touch on problems that are out of scope for our project. There are also two findings that have to be addressed by upstream or the platform (ModSecurity3 does not allow to disable backend compression and NGINX does not allow to inspect response bodies and there is nothing we can do in CRS to fix these shortcomings).

Lessons learnt: reports vs attack payloads

If you have participated in a bug bounty program before, you may have noticed the problem with the distinction of a report and an individual payload. A report is the smallest entity for the program. The report gets an ID, it gets triaged, it is forwarded to the developer and it’s also the base for the payout in the end.

However, bug hunters often listed multiple examples of similar payloads in the same report. Or they followed up with comments on the existing report and list additional payloads we did not detect. And sometimes they would not even be similar once we started to dig into them.

For a hunter it makes sense to add more content to a report, since it may allow to raise the severity and the exponential payout for the report. And it reduces the risk of a rejection as a duplicate since every additional finding makes the report more unique. Yahoo and Intigriti are used to this tendency and they advise the hunters to submit each finding separately.

However, it takes a big deal of knowledge of CRS to understand that a similar payload should in fact be detected by a different CRS rule. Naturally, this would have been our role in the program, yet we failed to keep up with the high pace and realized this problem only weeks or months after the program had ended.

Duplicate reports pile up on this problem. Even if a report is rejected as being a duplicate, we still have to look at them individually to make sure the fix of the original report also fixed the findings of the duplicate.

During the program we received 175 reports (including a low number of duplicates) and we extracted 511 payloads out of those reports. For CRS this was a source of endless pain.

Yahoo also tried to give us a kick start by paying the hunters additional bounties if they provided fixes for their findings. This also seems to be a model that gives open source projects an advantage: Paying for fixes in a bug bounty is uncommon as far as I can tell, yet the open source status of the code makes it relatively easy to identify the problem in the code and to provide fixes. I recommend to look into this option if you plan an open source bug bounty.

The pull requests we received this way were often ready to be merged immediately; others took some polishing before we could add them to the code base. I think we closed maybe a third of the reports with the pull requests we received.

The results

We survived the program and our rules are far stronger than they used to be a year ago. We have set up a tracker for security issues, we reduced thinking in reports and focus more on payloads instead. Every payload gets its own ID now. There is a policy to create a curl call first and we keep track of all conversations around a finding.

We also improved our tooling a big deal and I am proud to say that we never took the shortcut. Whenever facing a decision we decided to solve it in a clean fashion so it would not come back to haunt us. Our goal was clearly to profit from the bug bounty in a way that improved our project and our software for the long run. We also improved our tooling a big deal and we are very happy with the results.

It is unfortunate that the bug bounty delayed the CRS v4 release by a year. But this major release will be all the better because of the bug bounty.

A big thanks to all the people involved: Yahoo, Intigriti, the bug bounty hunters and our entire team.

Christian Folini, OWASP CRS co-lead

Christian Folini / [@ChrFolini]

Christian Folini / [@ChrFolini]